ARTICLES & WHITE PAPERS

Balancing Strategy and Oversight: How Boards Can Find More Time for the Long View

By Donley Townsend

Discussions about Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) compliance, CEO compensation, new exchange requirements, and the PCAOB have chewed up a great deal of board time over the past three years. Across the broad spectrum of corporate governance, emphasis has clearly been placed on oversight rather than support of management. While opinion is divided on whether the emphasis on oversight will prove beneficial in the long term, many chairmen, CEOs, and independent directors are asking how their board can become sources of strategic advantage. How can they provide the right balance of support and oversight in the shaping and implementing of winning strategies?

Select Board Members Capable of Dealing with Strategic Issues

While some directors may be superb executors of strategy, many good executives do not have a strategic business orientation. Some may be superb on a particular body of knowledge crucial to an organization's success, yet lack the ability to keep their focus at the strategic level.

Whenever possible, you want to keep these people off your board of directors. Look for directors with demonstrated success in strategy development and execution. Do they have broad interests and experiences? Can they frame issues within a larger context? Be sure you assess prospective directors' strategic interests and capabilities during the selection process.

Director Summary: Juggling strategy and oversight is a task incumbent on all boards of directors in the post- Sarbanes-Oxley era, and providing the requisite level of oversight while still functioning on a strategic level can be a difficult task. Directors and executives should consider these seven suggestions for effectively balancing these dual responsibilities.

If you find you already have some board members without a strategic sense, training and mentoring are two successful avenues to improvement. For some board members,a strategic planning seminar may provide them with the knowledge and tools to function comfortably in strategic deliberations. Others will benefit more from coaching by the chair.For some,both training and coaching might be beneficial.

Since selection is crucial, you must ensure that board members, whether insiders or outsiders, are committed to making a contribution to strong, effective governance and are able to devote ample time to their board responsibilities. Nothing will do more to keep board discussions strategic than locating directors with deep experience and an interest in strategy itself.

Emphasize Committee Effectiveness

Not all board work is strategic. There are subjects and situations where directors need to consider tactical details. It is incumbent on directors to give these matters proper attention without bogging down board meetings. One way to do this is through effective, cohesive work by the board's committees.

A positive outcome of the recent scrutiny on corporate governance is that boards have been forced to critically examine their committee structures. Many boards have streamlined their structures by pruning extraneous committees, and most boards have thoroughly examined and defined the responsibilities of each committee. Companies have also budgeted money so that committees have independent access to the expertise needed to fulfill their charters. What remains for many boards, however, is the development of specific work plans and deliverables for each board committee.

When committees do their work thoroughly, the board will maintain a strategic level. Obviously, this entails committees giving the requisite attention to details in their areas of responsibility and the chair and CEO ensuring company information is disseminated in a timely fashion. Committee effectiveness generally stems from:

- Members clearly understanding the committee's responsibilities.

- A committee chair who knows how to guide other directors.

- Committee members with the requisite levels of interest, knowledge, and skill.

- Guidance from the chair of the board on standards, expectations, and scheduling.

- A well-designed agenda for the whole board, such that the work of the various committees receives the appropriate attention from the whole board at the right time.

- Emphasizing committee effectiveness is a means of helping the board work effectively and efficiently. Given the expanded scope of board tasks post-SOX, excellent committee work helps guarantee that the board has meaningful time to devote to strategic matters.

Build a Board Team

Clearly, boards are not teams in any traditional sense; they meet infrequently compared to a management team, and their scope is limited. Historically, though, it has been easier for board members to be open and candid with one another because a rich, complex web of relationships generally exists among members. With a heightening emphasis being placed on importing independent directors, director relationships must be nurtured for boards to thrive. Before there is a real comfort level among all the members of the board, discussion naturally gravitates toward safe subjects that the individual members feel comfortable discussing. To be effective, boards must transcend this level of discourse.

Annual retreats are an increasingly common mechanism for building the relationships and trust needed for effective, strategic governance. Many boards schedule a dinner for the evening before each meeting for directors to learn about each other. One prominent Silicon Valley CEO refers to his company's board retreats and dinners as "the glue and grease" of good board work; glue to provide the right amount of cohesion, and grease to provide the lubrication that makes for the ability to candidly discuss emotionally charged subjects.

Ensure Solid Presentation of Corporate Strategy

Often CEOs unwittingly sabotage the board's ability to work at a strategic level by improperly framing strategic issues to their board of directors. If the directors cannot see where the strategy comes from and what the choices are, they quite naturally begin probing into the details, and a strategic discussion can deteriorate into a debate about minutiae.

Constructively involving the board in strategic initiatives requires effective collaboration between the chair and the CEO.

The CEO shoulders the bulk of the responsibility for keeping discourse on the strategic level. He or she can do this by:

- Defining and implementing a first-rate strategic planning process and informing the board of the what, when, and how of management's strategic work.

- Providing a broad context for strategy discussion. Often the CEO who combines deep industry expertise with ongoing immersion in strategy matters can forget that the directors (particularly independent outsiders) aren't familiar with the industry or market forces that shape the CEO's thinking.

- Making strategy work a process rather than an event. This does not mean reviewing the strategy at every board meeting. Rather, it entails the CEO apprising the board of his or her thinking on strategic matters through regular communications. Often, it also means collaborating closely with the chair (if the roles are split) to schedule board discussions of strategic issues over the course of several meetings culminating, perhaps, in a major review/ approval session at an annual board retreat.

Involve Board Members in One or More Strategic Initiatives

CEOs often feel board members do nothing so well as identifying mistakes discovered by another director or admitted by management. From the CEO's perspective, directors are far keener in exercising their oversight responsibilities than in a supporting role. Certainly Sarbanes-Oxley and new exchange requirements have pressured directors to heighten their oversight responsibilities. Directors and CEOs are both conscious of the need to keep directors from becoming managers, but recent events in the corporate world and the almost daily drumbeat of the business press points directors toward oversight, oversight, oversight.

However, involving directors in a small number of strategic initiatives is essential. This makes use of their considerable talents, develops their interest in and understanding of the company's strategic direction, and advances the initiatives themselves. Director involvement can cover a wide variety of tasks, from making contacts to mentoring executives. For venture capital-backed companies or start-ups, it is both a natural and necessary option. For larger, established enterprises, the chair and CEO may need to collaborate actively to find appropriate, meaningful ways for directors to contribute to strategic initiatives.

Historically it has been easier for board members to be candid with one another because a rich, complex web of relationships generally exists among members.

At one major engineering and construction firm, for example, the directors focused for a year on helping launch a strategic initiative to increase the firm's revenues from the federal government sector. Because management's knowledge and expertise were scant in the beginning, the board assisted with strategy formulation and action planning. Then each director took on individual tasks based on their respective expertise. One helped management understand the role of lobbyists and how to work effectively with them; another director helped revise the firm's bid response process to support the federal market initiative; a third introduced the responsible line manager to key officials in the executive branch and coached the line manager on how to tailor his approach to suit prospective clients.

At their annual retreat, the board, the CEO, and two other key executives reviewed the initiative's findings. Revenue results surpassed expectations. Managers credited the directors with playing key support roles. Outside directors were enthusiastic about their involvement, and everyone agreed the process had been a success.

Involving the board constructively in strategic initiatives requires effective collaboration between the chair and the CEO. However, the time and effort pays off with better execution of the initiatives, and a more knowledgeable, strategic board of directors.

Emphasize the Chair's

Leadership of the Board of Directors

Everyone who has taken the chair of a board of directors knows that it is a demanding task requiring a myriad of skills. The quality of a chair's abilities manifests itself in the board's achievements: balancing oversight and support; strategic and tactical deliberation; well-timed, thorough committee work; and deep collaboration with the CEO (when the roles are separate) in weaving together the threads of the board's work into a strong, supple cord.

Chairs can most effectively help their boards develop a strategic focus through their stewardship of the board's agenda. Close collaboration with the CEO (when the roles are separate) can ensure the board receives regular updates on strategy formulation and execution. For the chair who is also CEO, this may often entail overcoming his or her own defensiveness about management prerogatives. When the roles are separate, good chairs often devote some time and attention to diplomatically reminding the CEO to be forthcoming to the whole board about strategic decisions.

Focus on Fiduciary Duty

Many of the ideas presented above are rooted in the day-to-day realities of board and committee meetings. Taken separately or together, these ideas can help boards effectively balance oversight and support and maintain a strategic level of discourse. These ideas also provide mechanisms for companies to mine the knowledge, skills, and abilities of their directors without moving them into the realm of management.

Beyond these ideas, directors must focus on their bedrock duty of acting in the best interests of shareholders. This means ensuring that the company's strategy and operations point to a sustainable, competitive return on investment. Sometimes the easiest way to keep the board's deliberations at the right level is to focus on the directors' duties of care, loyalty, and good faith. Laws change, exchange requirements change, and ideas about best practices evolve, but the director's responsibility to do his or her best to act in the interest of shareholders is an immutable duty.

While these seven actions will go a long way toward strategic board deliberations, it's important to keep in mind that building a well-functioning board takes time. Balancing strategy work and oversight is an ongoing challenge because the balance changes with changing circumstances. What does not change is the need to deliberately carve out meaningful time for the strategic work of the board. If boards fail to perform the suggested actions, tactical oversight work will push strategic work to the periphery, to the company's long-term detriment.

Donley Townsend is president of Donley Townsend Associates, LLC, a Dallas-based consultancy engaged in recruitment and assimilation of directors. He may be reached at don@donleytownsend.com.

Executive Transitions: Improving the Success of Executive Appointments

INTRODUCTION

In July and September of 2017, two critically acclaimed films examined events in Europe in May and June of 1940. First, Dunkirk depicted the evacuation of the beleaguered British Army from France. Then, Darkest Hour dramatized the decisions behind that evacuation. In a way, both films show us the consequences of an executive transition.

On May 10, 1940, Neville Chamberlain, Prime Minister of Great Britain, had just lost a confidence vote in the House of Commons. Late that afternoon, the man who served as the equivalent of today’s Press Secretary stepped out the front door of 10 Downing Street to speak with a handful of reporters gathered there. He made only this brief statement, “His Majesty, the King, has sent for Mister Winston Churchill to ask him to form a government.” Thus began one of the most important executive transitions in history. Churchill quickly formed an all-party cabinet. Three days later on May 13, he offered his stark assessment in his first speech to Parliament as Prime Minister; “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat.” He then outlined his basic plans for British resistance to Nazi Germany. Much remained to be done and was done. Our world owes much to Churchill’s ability to take charge of new responsibilities.

Each day around the world, hundreds, if not thousands, of executives in all types of organizations move into new roles. In every instance, the organization expects improved success. And the individual making this personal transition has high hopes for gains in knowledge, skills, prestige and, frequently, wealth. Many of these transitions are reasonably successful. Incremental improvements are made. Companies succeed a little better. And individuals prosper a little more. Sometimes executive transitions make an important impact, for good or ill, on the performance and prospects of a large enterprise. In 1993, when Lou Gerstner came from RJR Nabisco to take the helm of IBM, many believed that the computer powerhouse had no options but to break itself up, that there was no way forward for the giant IBM. In fact, under Gerstner’s predecessor, John Akers, plans for such a breakup were underway. Gerstner decided soon after he began immersing himself in IBM that there was a need for a company that could integrate information technologies for customers. He halted the “disaggregation” plans, focused keenly on execution, and emphasized services. When he retired in 2002, Gerstner was hailed for leading IBM to new strengths and successes not to a breakup.

A few years after Gerstner moved to Armonk, New York to lead IBM, Apple computer turned to its co-founder, Steve Jobs, asking him to return and lead Apple once again. In 1997, Jobs became CEO after a 12-year period that saw him found Next Computer and acquire Pixar. Jobs began his reimmersion in Apple by reviewing every product program underway whittling 350 efforts down to 50. Within 10 years, Apple Computer would become the most valuable company in the world. More recently, Pieter Nota led a successful turnaround of Philips Consumer Lifestyle sector, a combination of two formerly separate entities, small domestic appliances and consumer electronics. Nota joined Philips in 2010 from Beiersdorf where he held a staff role as Chief Marketing and Innovation Officer. He found Philips Consumer Lifestyle sector in poor shape. Recently though, the sector announced its 10th consecutive quarter of strong revenue and profit growth.

These three well-publicized transitions represent a tiny fraction of the transitions taking place every day. Their careers demonstrate that those who rise through many challenges to reach the top rungs develop and refine the skills of successfully taking charge of new assignments.

Unlike these, not all go well. J C Penney showed CEO Ron Johnson the door just 17 months after hiring him away from Apple where he had led the rollout and successful growth of Apple stores around the world. Whatever magic he had in Cupertino didn’t travel to Plano. Penney almost tanked under his leadership. The same J C Penney hired Catherine West from Capital One Financial in 2006 to be their Chief Operating Officer. She lasted five months.

At Donley Townsend Associates, we have an opportunity to work with senior executives as they plan for and implement executive transitions at the top levels of business, higher education, and government. From this vantage point we’ve talked in-depth with corporate CEO’s, Managing Directors, Board Chairmen, university presidents, heads of government agencies, general managers and Human Resources leaders. We’ve gathered their thoughts about executive transitions, good and bad. Their views on the transitions of others and their often intensely felt stories of their own transitions shaped our perspective.

As we gathered these stories, we began to look for the characteristics of highly successful transitions and the characteristics of failed transitions. The stakes for an enterprise, the gap between a highly successful transition and a failed transition, are huge. While certain themes seemed easy to spot, a more rigorous investigation seemed warranted. Over the course of five years (1998 to 2002), we interviewed over three hundred senior leaders. These executives worked in a wide range of industries and included leaders from

Belgium, France, Germany, Great Britain, Japan, Mexico, the Netherlands, Sweden,

Switzerland and the United States. While often wide-ranging in scope, each of these interviews was structured to gather information about the actions the new executives took on entering new roles, and then to probe beneath the surface to determine which actions worked and which did not.

From these in-depth and revealing interviews, we distilled the essential elements of successful transitions and the practical steps of implementing them. Our view encompasses actions that highly successful executives take when they transition to a new role and actions that organizations take to help new leaders make transitions. Executives have been very open about what worked for them, and many looked back on their career to describe how they learned from early transitions such as their first leadership role or their first general management role. We also found, somewhat to our surprise, that the executives we talked to were very willing to discuss the mistakes they had made in transitions during their careers, how they learned from their missteps, and what they will try to do differently in their next move.

In the years since we published our initial white paper on executive transitions, we’ve tested the Six Keys in a broad range of coaching assignments working closely with executives to help them make successful transitions. The engagements include COOs, CFOs, CMOs and a number of newly created general management roles. This decade of coaching work convinces us of the value of the Six Keys, but we’ve also learned from highly successful executives some important lessons that fall, perhaps, into the personal arena. Transitions are difficult and demanding. Those who perform best know how to take care of themselves even in stressful times. They get sufficient sleep; they exercise regularly; they maintain a healthy diet. They know they must be in the best possible mental, emotional, and physical condition so they can bring the focus needed to crucial decisions and interpersonal interactions.

SIX KEYS

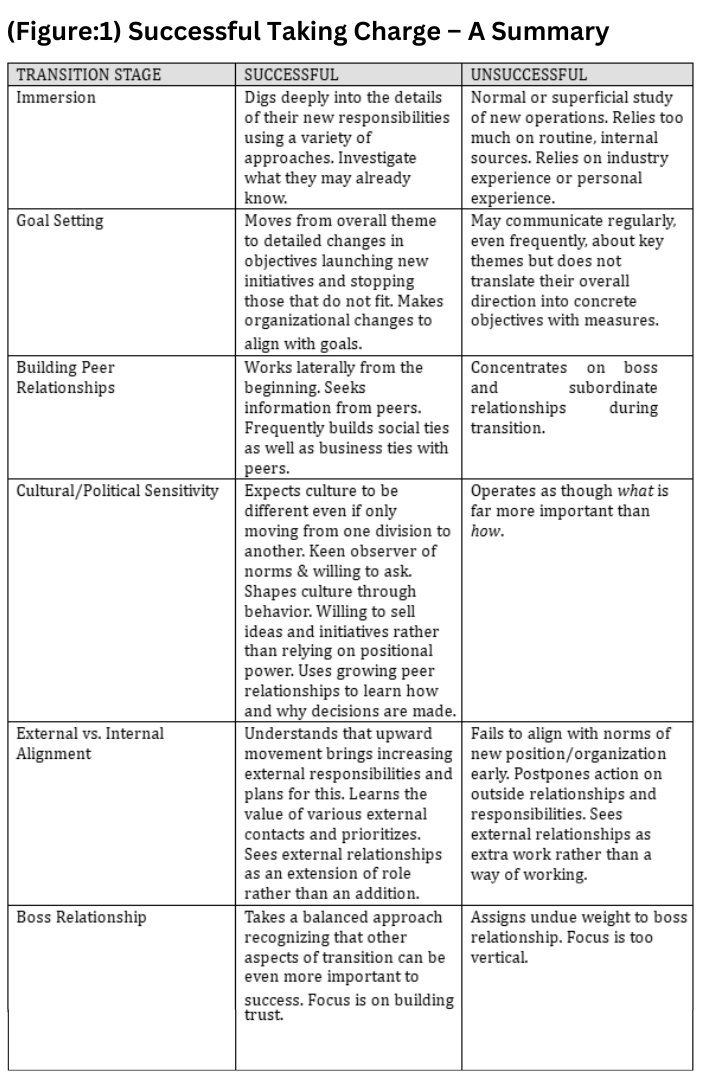

Our analysis points to six key transition hurdles; immersion, goal setting, building peer relationships, developing a cultural or political sensitivity to the new organization, finding the right external vs. internal alignment, and, finally, building a productive relationship with the boss. (See figure 1.)

IMMERSION

Immersion describes the new leader’s first three to twelve months in a new role. Anne

Mulcahy’s appointment as CEO of Xerox illustrates. When she took charge on August 1, 2001, Xerox owed $17 billion, and its credit rating was in the tank. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) had just launched an investigation of the company’s accounting. In the previous two years, its share price dropped from $63.69 to $4.43.

Was Anne prepared? In her own words, “I never expected to be CEO of Xerox. I was never groomed to be CEO of Xerox. It was a total surprise to everyone, including me.” Anne was fiercely loyal to Xerox. She started her career there in Sales and worked in Marketing and Human Resources as well. As CEO, she went into learning mode. In her first 90 days she travelled over 100,000 miles visiting Xerox factories, sales offices, and customers. At the same time, she immersed herself in learning about debt, inventory, taxes, and currency to understand the impact of decisions on the balance sheet. In two years, Xerox returned to profitability.

Not all transitions are as dramatic as Anne’s yet during this period, an executive must master a tremendous quantity of new information about the specifics, the details of their new area of responsibility. For a business general manager there may be a product line, its competitive strengths and weaknesses, new products in the pipeline, factories with labor problems, etc. For a university president, there may be a curriculum to build, funds to be raised, and the competitive threats of distance learning and expanding for-profit educators. For a government agency head there may be intricate legislation to master as well as complex relationships with other agencies to learn. In every case, whether through promotion, transfer, or appointment from outside, new leaders in executive positions face a daunting amount of information to master.

In the most successful immersions, the new executive commits the time and energy to dig into the details of their new organization and beyond that to the underlying technology, products, services and laws. During her first year as CEO of Xerox, Anne Mulcahy worked all or part of every weekend. One CEO of a well-known Silicon Valley technology firm, recruited from another company, studied the underlying technology of his new company’s products by reading the graduate textbooks on the appropriate engineering and scientific subjects. Most general managers spoke of the need to learn by seeing. One CEO mentioned that he learned early on that “a desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world”. Successful transtitioners go out in the field “to work beside people who work at the customer facing level”. Another CEO (of a Fortune 100 energy firm) prepares individualized To Do lists for all new subordinates. He labels them

“Ninety Things in Ninety Days”. Each of these lists is carefully tailored to provide breadth and depth learning as well as introductions to key external relationships. And, importantly, this effort on the CEO’s part endorses the immersion period. During the immersion stage, executives typically begin with a focus on their immediate responsibilities then move to an understanding of the influencing factors; they move from technology, to products, to markets, to trends or from understanding the plant managers, to labor contracts, to overall labor relations, to comparative manufacturing costs in other countries.

The immersion period for highly successful executive transitions also naturally includes meeting and learning about a wide variety of people. This includes bosses, subordinates and peers. During the immersion phase, the first three to six months, new executives must carefully assess their subordinates, and, in many cases, they must assess candidates for key subordinate positions. This learning process is fraught with emotional issues and undertones. New subordinates frequently include disappointed aspirants for the new executive’s position. Often there are old or existing rivalries between subordinates who will want to pursue their own goals and ambitions. These same individuals will have different evaluations of the on-going work of the organization. How do the executives most successful at taking charge make their way through this?

They often begin with one-on-one meetings with each subordinate. In these initial meetings the new executive asks about the subordinate’s role, objectives, key projects and, very importantly, aspirations. These conversations enable the new executive to gauge individual talents, understand the working structure of their organization and the level of collaboration. The executives best at taking charge follow these meetings with discussions further down their organization. As one of his first moves, Pieter Nota at Philips wrote an open letter to 700 people in the Philips Consumer Lifestyle sector asking what was working and what wasn’t. From the responses to his letter he learned which components of the organization weren’t functioning well, the problems caused by underinvestment in some key product areas and a lack of empowerment in the sales force.

These three key findings became priorities for which he found solutions in his first year. Other executives make similar discoveries by holding brown bag lunches with small groups of supervisors and individual contributors. In some cases, they conduct skip-level, one-on-one meetings. As mentioned above, successful executives spend time with the people who do the day-to-day making, selling, and servicing during (and after) their taking charge phase.

The most successful transitions also include reaching out to people outside their organization whose views could be helpful. These outside contacts help new executives quickly sift the true from the somewhat true. Conversations with outsiders…friends, bankers, attorneys, auditors, consultants…help the new executive organize the learning, to make sense of the tremendous amount of new information. The key element of the immersion phase is learning the facts, the details.

Organizations can (and some do) provide a roadmap. The most helpful provide easy access to information and introductions to key individuals. Some appoint a formal or informal sponsor to provide a sounding board an interpreter…someone who can provide helpful context for the new executive. Yet, no matter how much help is offered a successful immersion depends on the new executive because learning styles are so personal. The most successful transitions belong to those executives who spend the extra hours to pour through reports, literature, policies, processes…all the nitty-gritty of their new responsibilities during the first three to six months. Successful executives know their preferred learning style and organize their work to mesh with their strengths. During transitions though, the most successful executives consciously and purposefully step outside their preferred style to take in as much as they can as quickly as they can. Listeners become readers. People oriented executives pour over financial reports and customer data. Numbers people push themselves to have lots of meetings and listen to lots of people.

Transitions to new responsibilities are periods of intense work. Many executives we spoke to mentioned experiences like Anne Mulcahy’s. To be able to use what they learn in their immersion work, the most successful executives build or consciously maintain times for contemplation and making meaning from their experiences. Raymond Kethledge and Michael Ervin interviewed Marine General and Secretary of Defense

James Mattis for their book, Lead Yourself First (Bloomsbury: 2017). He told them, “If I was to sum up the single biggest problem of senior leadership in the information age, it’s a lack of reflection.” Reflection allows executives the opportunity to draw conclusions, to decide when and where more information must be sought, to form solid judgments about their organizations, and to gather strength and perspective as they press on.

GOAL SETTING

Goal setting refers to the process whereby a new executive develops, communicates and gains support for a new vision for the organization. The goal-setting phase of an effective transition is the new executive’s opportunity to establish and communicate a broad view of a better future. While detailed strategies, tactics, programs, and plans take a while to shape and unfold, the most successful executives move quickly to articulate in broad terms how the future needs to differ from the past. One new president of a paper company described it this way; “I gave up a lot of important-looking things and erred on the side of being brutally simple. I focused on only two themes – quality and throughput. Everyone knew what was important, and that made our energy productive.”

When Paul Pressler left his job as head of Walt Disney Parks and Resorts to become CEO of Gap, Inc., he faced a tough transition. Gap, the world’s largest specialty-apparel retailer, had 28 straight months of declining same-store sales. It was losing money and its debt had plunged to junk bond levels. And, Pressler had no experience in retail, fashion, or apparel. As he began his immersion and goal setting work, he asked the company’s Communications department to create a weblog for him accessible to all Gap employees. There in journal fashion he posted all his activities and wrote about what he was learning. Summarizing his travels and store visits allowed him to share his sense of humor as well as his passion for learning. As his transition advanced, he began to formulate and communicate key themes – understanding Gap’s customers, improving logistics and inventory systems to free up cash, and making Gap a great place to work. His communications facilitated his goal-setting work.

Once the broad themes are in place, they can move on to the more discrete objectives with a visible context. Few if any executives these days come into a new role with a mandate to keep things as they are. Organizations expect leaders to take action to make things better. And the time horizon for making improvements is growing shorter in most firms. At the executive level, new leaders generally enjoy a fairly broad mandate. It is up to them to translate this mandate into the specific programs, initiatives and measures that they believe will lead to the fulfillment of their mandate. In the late 1980’s Thomas Gilmore noted that “leaders absorb uncertainties and transform them into directions that give meaning to the work of others”. Executives who make the most successful transitions focus carefully on setting and communicating their goals and they visibly lead the work of translating goals and themes into specific, detailed programs for each area of responsibility.

Frequently, this work begins before they formally assume their new responsibilities. One senior operations leader for a semiconductor manufacturer spent his flight time between California and Europe developing the high-level goals for the troubled plant he was sent to turn around. He knew he needed to strike an ambitious tone to help galvanize the organization for the hard work ahead. He knew that big improvements were needed to justify the investment made in the facility. His initial goal setting communicated the size of the task and provided the broad framework for dozens of specific objectives for the departments of the plant.

Once onboard in their new roles, the most successful executives articulate their key themes repeatedly as they begin their immersion work. Like Steve Jobs when he returned to Apple, executives in successful transitions dive into detailed reviews of the programs and plans currently underway in their new organization. This approach contrasts markedly with executives who have unsuccessful transitions in which the executives tend to repeat their key theme until it becomes almost a mantra while frequently omitting the detailed work of aligning discreet objectives with their vision.

Once they’ve established an overarching goal, executives who are most successful at taking charge begin their goal setting work using their careful review of current plans and programs in the organization. This process provides them with opportunities to meet members of their organizations typically in a well-planned combination of staff meetings, off-sites, and one-on-ones. The most successful executives approach all these meetings thoughtfully and carefully. Pieter Nota at Philips describes the first off-site meeting after he began his transition; “This is where we put the issues on the table. Two things remain clearly etched in my memory. One is a no-holds-barred conversation on team loyalty, which emphasized the importance of our values, our core purpose, and the essential notion of trust. The second is the introduction of some critical new thinking on how to improve the quality of our operations and implementation capabilities. We ended up spending three hours talking about the past, clearing the air, and gaining a better understanding of each other.”

In the goal setting phase, the new executive learns how goals have been set and the assumptions behind those goals. He/she begins to develop relationships with subordinates and some of their subordinates, which move beyond the scope of the fact finding in the immersion phase. The new executive also begins to develop a sense for what his organization is capable of, how far it can stretch. The most successful executives want to know right away their new organization’s strengths and weaknesses.

As the detailed review comes to a close, the successful leaders gather their organizations to revise and update their goals and plans. In the most successful executive transitions, this is as much about saying “no” as saying “yes”. During his first five years as CEO of Proctor & Gamble, A. G. Lafley led the company to a 30% increase in revenue and a

70% increase in profit. One of his first decisions was not an investment but the axing of $200 million in technology projects and regional marketing campaigns. Describing his transition to CEO, Lafley said, “Be clear on what you won’t do – what needs to stop. Most human beings and most companies don’t like to make choices, and they particularly don’t like to make a few choices they really have to live with.” Executives who make successful transitions are almost twice as likely to communicate explicitly what to stop.

They also introduce new measures, key indicators of how well their organization is meeting their new goals. Frequently, like Nota, the most successful new executives use this forum to begin disclosing more about themselves. They provide information about who they are, what they hope to achieve, how they manage, what’s important and what’s not. They also work to learn more about the key people on their teams. They seek to understand their histories, goals, personal values and aspirations along with all their perspectives on the organization. Then they link the new goals and objectives to the overall theme they communicated in the beginning.

Thus, the goal setting work of the transition provides them with the foundation for trust, that important combination of results, integrity, and concern that marks high-performing teams.

BUILDING PEER RELATIONSHIPS

Successful executive transitions are broad as well as deep. In fact, one of the key differences between successful and unsuccessful transitions is breadth. The most successful executives reach out energetically to build strong, positive relationships with peers. Less successful executives focus vertically on their boss and their subordinates.

How then do the most successful transitions do the work of building relationships with peers? The answer depends in large part on the role the executive is entering. Those coming into staff functions have the advantage of positions that provide services to other parts of the larger organization. One top Human Resources executive at a medical instruments firm in the Midwest noted that a key element of building relationships with his peers was providing an especially high level of service to their requests during his first few months. He followed through personally on their requests thereby increasing his opportunities for interaction with them and providing him with insights on the performance of his key subordinates and his organization. He recognized that performance on the more mundane things served to build his credibility. Another executive, entering one of the world’s largest financial services organizations in a role with great influence over executive succession and development realized that she could and would be viewed with suspicion by many in the company’s top ranks. Recognizing the sensitive nature of the role, she built trust by asking her peers for advice and counsel. This approach tapped a vein of helpfulness that was a strong part of the company’s culture. It also flipped expectations. By seeking advice rather than giving it, the new executive found that her peers opened up readily. She established productive relationships and her peers “voted her in”.

Executives entering general management or line roles have a tougher time. One executive in our study joined a large Midwest based retail company to head Logistics & Distribution. His organization was formed by taking these functions away from the divisions where they had historically resided and centralizing them under his leadership. Not surprisingly, he faced some obstacles to building strong relationships with peers who felt they had lost something to him. Because he was brought in to make major improvements to the logistics and distribution functions, he possessed in-depth technical expertise. Recognizing that this could become a disadvantage in his efforts to both make improvements and build relationships, the new executive carefully framed each of his initiatives for each product division demonstrating the positive impact it would have on that division’s performance. This approach meant extra work for him and his people to prepare financial analyses and presentations broken out for each division. But it provided a way for the new executive to build relationships through one-on-one meetings where he talked about his initiatives and showed the impact. These meetings allowed him to triple check his facts and gauge potential opposition. He was able to sense what might make his peers defensive. In this way, he was able to accomplish what he had been hired to do and be accepted as part of the senior team.

In another instance, a fast growth high technology firm in the Southwest hired a Vice President/General Manager to lead a new state-of-the-art engineering and manufacturing facility. The new executive was superbly qualified through experience, industry knowledge and drive. He also possessed exactly the management style the president wanted for the new facility, a project that represented a material capital investment. The new executive concentrated on building his organization and on his relationship with the president largely ignoring his peers and the group executive between him and the president. The president called him in frequently, listened to progress reports and praised his efforts. His subordinates took readily to his approach and the opportunity afforded by the company’s investment in the facility. Morale, energy, and engagement on new objectives were all high. Yet, when he encountered some inevitable and normally manageable bumps, he had no allies among his peers. Within 14 months he was fired; the new facility’s workforce was demoralized and relationships among the company’s top six executives were visibly damaged. Within a year, the ripples from this failed transition led to the company’s acquisition through a hostile takeover.

Many line executives and general managers note that disparate locations and different businesses can make building peer relationships more difficult. However, the executives with the greatest success in new roles use every means available to reach out to peers. They look for opportunities for social interaction as a way to build peer relationships; they use conference calls and emails. They seek opportunities to use task forces and other ad hoc structures to bring them into contact with a broad range of colleagues. Successful executives have realistic expectations about peer relationships. One senior executive in a top manufacturing job said, “In a couple of cases it’s like oil and water. I don’t mix well with two peers; I have good relationships with most; and there are two or three where I’ve formed great relationships quickly. I accept that not all of them will be great.”

Developing Cultural & Political Sensitivity

One CEO who successfully negotiated transitions into four large public companies during a distinguished career summed up his experience by saying, “one thing is for sure; don’t underestimate the differences in company cultures. They are more different than they are alike. In a way what helped me the most was learning from early mistakes. I learned not to come in with a ‘missionary complex’, thinking I was smarter than I was.” Another CEO noted that every organization has a certain momentum when you join it and if that momentum is, on balance, positive, then you must make your ideas somewhat compatible with the momentum. In his experience this meant taking the same care in selling ideas inside the company as he would in addressing a major opportunity with a prospective customer. In addition, he tried to find influential individuals to help champion new ideas. He summed up his approach by noting that even when you are in one of the top jobs, you must sell your ideas and “there better be some meat on the bones when you introduce them”. He expanded on the selling concept by noting that he liked to view objections or resistance from people in the company similar to the way he would with a prospective customer, as an opportunity to fully understand their views, learn from their perspectives and modify his views where needed. “Even with opposition you must believe in your ideas and keep coming back and selling them in a way compatible with the culture”.

Developing cultural and political sensitivity is easier for executives whose roles put them in regular contact with customers, suppliers and other outsiders who know the company. These outsiders provide insights about the organization that take much longer to acquire from insiders. This is a key finding for executives entering new organizations in staff roles. Among CFO’s, CIO’s, General Counsels, HR leaders, etc., the most successful are those who spend time with their companies’ customers and suppliers as well as in the field or plants with the company’s sales, service, and manufacturing workers.

Political sensitivity means learning how decisions are made and carried out within the culture of the organization, and how the work is done. Successful transitions go to executives who link their initial successes to issues where others win as well. Successful transitions also go to executives who do the work of immersion and goal setting well. Executives who depend on culture change as their key leadership tool seldom enjoy sustained success.

Internal/External Alignment

At and near the top of organizations, the web of important relationships with people outside the company expands significantly. After a career of working inside an organization and dealing only with slices of outsiders, executives near the top find their schedules brimming with business and social meetings with customers, suppliers, lawyers, bankers, civic officials, politicians, regulatory consultants, strategy consultants, accountants, public relations consultants, investor relations consultants, etc. There are also requests for their time and attention from cultural and philanthropic organizations. In a number of cases there are outside board memberships that require time and attention. For any new executive, the time management challenge can be daunting. For an executive coming from the outside the challenge is even greater. First there are the challenges presented by their immersion phase. Then there are norms to learn regarding outside board memberships and cultural and philanthropic endeavors. Frequently, the differences can be large.

One business school dean who came from industry was thrown off track for months by these differences. He brought a set of assumptions from a highly successful career in a Fortune 100 firm where he rose to Chief Operating Officer. All his experience was in a culture that stressed deep concentration on improving your own organization before engaging outside the enterprise. First one, then the other was his viewpoint developed over 30+ years of operational success. He set out with vigor to improve the business school based on the problems and challenges identified during the selection process. For him it seemed normal to refuse invitations he viewed as social or ceremonial while concentrating on a turnaround. Because he was the first business leader to take a key role at this university, months went by before he, the president and the provost identified the situation and arrived at an understanding. The president, provost and trustees wanted an action-oriented leader. The new dean wanted very much to succeed in this new role that he viewed as an opportunity to give back to a business world where he had enjoyed great success. Finally, the three glimpsed the problem. For the university community, the events the new dean saw as social were part and parcel of how work got done. The organization wanted broad engagement even though it meant a slower turnaround at the business school.

After this painful transition, all the people involved had a keen appreciation for the importance of understanding an organization’s norms about the external/internal balance for top leaders. Unfortunately, the interviewing and selection processes in most large organizations avoid discussion of relationships with outsiders, focusing almost exclusively on job related issues and inside the organization topics.

External relationships are important at the upper levels of any organization. When an executive grows up in one company, there are usually informal mentoring mechanisms used to introduce rising executives to appropriate external connections. Executives coming from outside, through recruitment, acquisition or assignment to a joint venture, need to explicitly learn the new organization’s ropes and then make appropriate time for external relationships. It’s no wonder that 60-hour weeks are common during transitions.

Boss Relationship

Through the selection process, hiring executives and candidates for executive positions play out an elaborate ritual of behaviors designed to fill a position with a person of outstanding capabilities. Once the selection process is over and the new executive starts, a new relationship must be built. The new executive must understand and respond to the boss’ way of working. Frequently, the switch from candidate to employee, with the different behaviors required, shocks new executives.

Most executives coming into new roles pay particular attention to their relationship with their boss. Almost everyone intuitively grasps the importance of understanding their boss’ expectations and acting on them. Our experience indicates that at the upper level of organizations, building a solid relationship with one’s boss is far more than just carrying out tasks and making improvements. One division president, who shared his experiences on several transitions, summed up his lessons with the conclusion that “building trust is the essential ingredient. This requires delivering on commitments, demonstrating that you are learning your role and the challenges you face. It also means moving beyond defined roles to become a person others rely on for counsel and an objective viewpoint.”

For those in the top executive role whether president, CEO or Managing Director, there is the complex challenge of reporting not to an individual but to a board of directors or trustees. (See figure 2.) Aside from the obvious multiplicity of relationships there is the very limited and formal interaction inherent in conversations scheduled months in advance for a set, limited time and following a prearranged agenda all under the influence of by-laws, statutes, exchange requirements and governance best practices. It’s a tough environment for anyone to build productive relationships in. The legislative changes and new exchange requirements in the United States have made it even more challenging and time consuming for the CEOs of U.S. public companies to build these relationships with the individuals on their boards.

There’s another critical aspect of the boss relationship that falls a little outside the actual process of taking charge. Leaders need to be skillful and careful during the selection process before they’re even named to a new position. Whether internal promotion or external recruit, negotiating and fully understanding the mandate is crucial to success. Often bosses, including boards of directors, are less than clear about what they expect within what timeframe. Often executives assume a broader mandate than the boss has in mind. So, it is important to understand clearly and reach agreement with the boss (or bosses in the case of a board) about the critical few objectives to be accomplished in the first 12 – 18 months. Once the mandate is clear, the most successful executives leverage whatever time they have before taking up the new job to learn about products, technologies, markets, and customers. They also learn as much as they can about the history and capabilities of the organization they are about to lead.

CONCLUSION

Transitions take place every day. New leaders take over. Organizations and individuals want and need for these transitions to lead to improved operations and results. Our work with top leaders shows that those with the right skills can make a big, positive impact on the enterprises they lead. Clearly, leaders who possess good taking charge skills will have opportunities never seen by others.

For information on Executive Assimilation Coaching please contact:

Don Townsend

Donley Townsend Associates, LLC

North Central Plaza Three

12801 North Central Expressway

Suite 1220

Dallas, TX 75243

o) 214-393-4499

c) 214-213-5274

don@donleytownsend.com

Director Assimilation: Helping the New Director Become Effective

By Donley Townsend

Personal liability, term limits, increased independence, more rigorous evaluation- these areas of growing concern are contributing to increased turnover on boards of directors, the one area of business not previously racked by ever shortening tenure. With organizations changing the composition of their boards with greater frequency, more and more directors are new in their roles.

New organizations face an even more dramatic challenge. They must attract competent directors and then assimilate them so they can provide effective guidance to the firm during a dynamic, often volatile, start up. How can organizations help new directors learn what they need to know to be effective in their ever more challenging responsibilities?

To understand how CEOs, chairs, and directors are approaching the assimilation of new directors, we interviewed top corporate leaders in a variety of industries including technology, financial services, consumer packaged goods, energy, manufacturing, healthcare, and a broad range of professional services from information technology to engineering. A number of the men and women we spoke with, in fact the majority, had multiple perspectives. Some serve as outside directors on multiple boards and provided keen insights based on the practices they've experienced in different companies and industries. Some are CEOs at one firm and serve as outside directors on other boards. Most brought additional insights from university and other not-for-profit boards on which they serve.

Director Summary: Key practices in assimilating a new director into a company's corporate culture are to set the competitive environment; offer details about the company; describe and explain specific board practices; provide an ongoing external frame of reference; and build personal relationships among board members, the CEO, and the chair.

Our conclusions provide a practical roadmap for business leaders in building high performance boards of directors, strengthening corporate governance and establishing an effective balance between oversight and support.

Five Keys for Effective Director Assimilation

Once a new director agrees to join the board, how can the organization help him/her become effective? Key practices are:

- Set the competitive environment.

- Detail the company.

- Describe and explain specific board practices.

- Provide ongoing external frame of reference.

- Build personal relationships.

Set the Competitive Environment

Begin by helping the new director understand the company's broad, as well as specific, industry segments, markets, key competitors, customers, and suppliers. Describe the regulatory environment and the technologies that are essential to the business's success. Make sure the new director knows the forces that shape the environment in which the company operates. Be candid about the competitors that represent the bigger threats. The 80/20 rule provides a good framework for helping new directors understand the external forces on the organization. Who are the 20 percent of your customers that probably account for 80 percent of your sales and profits? Similarly, who are the 20 percent of your suppliers who probably receive 80 percent of your spending?

The CEO of a Silicon Valley technology firm with a wide product range addressing a number of disparate markets described this element of director assimilation: "We planned a six-month acclimation rather than an event because of our complexity."

Once grounded in the firm's external competitive environment, a new director is ready to develop a fine-grained understanding of the company's strategy-its plans for succeeding in its environment. Interestingly, few organizations focus any attention on providing an industry context for the new director. Most simply plunge into facts about the firm itself. That should be phase two, the details about the company.

Detail the Company

New directors, chairmen, CEOs, and nominating committee members all understand the need to provide the board's new member with information about the enterprise. Most organizations provide something. Yet all too often, the materials, the briefing book, are nothing more than an amalgamation of what the corporate secretary or the general counsel thinks a new director might want.

Chairmen, CEOs, and nominating committees need to give more attention to understanding the requirements of a new director and preparing materials and activities to meet the new director's specific needs.

One new director, a senior line executive at a refining and marketing company, recently joined the board of an exploration and production company. He described the orientation he received as "multiple portals into the company." His election coincided with the company's annual meeting where the "presentations made a good foundation." However it begins, this phase of director orientation should provide the new director with a thorough understanding of the company and the challenges and opportunities before it.

A former CEO who sits on the boards of three Fortune 100 companies found "a two-and-one-half-hour strategy presentation before the first board meeting I attended" extremely valuable. That first board meeting with her new board colleagues followed soon after the strategy briefing, and was followed quickly by an all-day orientation, which included one-on-ones with the general counsel, the HR executive, and senior management. With this three-part introduction, she felt comfortable in her ability to begin contributing effectively to the board. Keep in mind, though: this new director had been the CEO of a multi-billion-dollar publicly traded company and an outside director at two other Fortune 100 companies for more than 10 years before she joined this board.

Directors with less experience need a different orientation, one that balances learning through reading, listening, and seeing. For a new director with little or no previous experience on the board of a public company, begin by providing more reading material than anyone would ever want, including:

- Bylaws and articles of incorporation.

- 10-Qs and 10-Ks for the last three years.

- Board minutes for the last two to three years (so the chain of decisions is clear).

- Organization charts (including the existing board and its committees).

- Proxy statements.

- Corporate governance guidelines.

- Code of ethics and anti-insider trading policy including section 16 reporting procedures.

- Disclosure controls and procedures.

Make sure the new director knows the forces that shape the environment in which the company operates. Be candid about the competitors that represent the bigger threats.

In a box, all this reading material could put the new director's back in jeopardy. So consider providing it in CD-ROM format if possible. In this way, the odd hour or two on a plane can be used by the new director for learning about the company.

While all this reading is underway, supplement the learning with conversations. One new director appreciated a lunch with the CEO that allowed him to ask questions on what he was learning, and continue building a personal relationship simultaneously. Soon after, the members of the nominating committee called to welcome him to the board and fill him in on company business. These calls and meetings prove especially valuable when part of an overall orientation plan where each board member covers a specific topic, while beginning the process of building personal relationships.

The third leg of the orientation for learning the company involves seeing. Virtually every director who had site visits or plant tours as part of their assimilation process gave high marks to the experience. Whether it is a tour of a manufacturing plant, a brown bag lunch with a dozen or so engineers, or a coffee meeting with customer service representatives, new directors place a high value on opportunities to visit factories, key development centers, or customer service centers. Not surprisingly, employees like it as well, getting the rare opportunity to meet a director of the company in an informal, give-andtake environment. In addition to orientation for the new director, such meetings provide informal investor relations since, in many companies, employees are, in aggregate, significant shareholders with the potential to invest more in the future.

The thrust of any orientation effort is to improve the effectiveness of new members of the group; it is good for them and good for the boards on which they serve.

Reading, listening, seeing...good director orientation hits all three as the new director goes through an immersion process learning the new company.

Describe and Explain Specific Board Practices

Perhaps nowhere does good orientation matter more than in the practices specific to an individual board. Learning how to be effective and make your experience and expertise count when you join a new group is always a challenge. When you are an independent outsider in a group that meets for a day or so every couple of months, the challenge becomes greater. And isn't the gist of much of the recent legislative changes and the new exchange requirements centered on having independent outsiders on the board and making sure they are doing a great job of being a director? Unfortunately, this aspect of orientation is frequently overlooked. After all, in the not too distant past, directors were chosen in part because they were already well known to other board members and the atmosphere was collegial from the beginning.

Filling the new person in on how the board operates and why it works that way helps the new director contribute and the whole board perform effectively and efficiently.

Consider these actual situations to understand why it is important to let new directors know the scoop on how the board actually operates.

- A major healthcare company began using presentations to the board for development and succession planning purposes. At each meeting a manager would make a somewhat formal presentation to the board on an important topic. For most of these high-potential managers, this was their first interaction with the outside directors. A new director joined the board about six months after these presentations began. He was also on the board of a consumer packaged goods company where presentations by senior managers were a long-established practice. There the presenters expected and faced tough questions from board members throughout their presentations. The norm was a vigorous give-and-take exchange between the presenters and directors. Not surprisingly, the new director interrupted the presentation at the new board to ask a pointed question. No one had told him this board's norm was to hold questions to the end of the presentation and then let the chairman begin the questions. The presenter was thrown off and so were the other directors. All the embarrassment could have been avoided with a brief review of the agenda by a mentor with the new director before the meeting.

- Another avoidable situation arose when a new director came to his third board meeting (about six months on the board) only to find himself in the midst of a contentious board self-evaluation process which included an effort by the chairman to seek the retirement of a poorly performing board member. The new director was unfamiliar with the evaluation process and knew nothing of the situation surrounding his fellow director (other than that he missed most meetings). Again, a simple process of showing the ropes could have made the meeting more productive and avoided embarrassment.

Of course, directors ought to be thick skinned and adept at reading groups and situations. Indeed, the vast majority are. The thrust of any orientation effort, though, is to improve the effectiveness of new members of the group; it is good for them and good for the boards on which they serve. Successful orientation in this area requires only that one experienced director takes time to think through what is unique or unusual about the way the board operates and then takes the time to fill the new person in. Ideally, a director with several years experience and service on multiple boards takes on this task.

Provide an Ongoing External Frame of Reference

It is natural to focus the attention of a new director on the company he or she will help govern. It is also natural to shine a light on the strategy and other topics traditionally on the board's agenda. But with corporate governance taking a broader view, it makes sense for new directors to rapidly learn about the company's key external constituencies from two perspectives:

- External relationships important to the company, and

- External forces shaping boards and affecting individual directors.

Introduce the new director to the firm's outside audit partner, the outside counsel, and other consultants with whom there are important ongoing relationships. Conversations with commercial and investment bankers, as well as the external auditor, can be logically coordinated by the CFO. Through a series of four or five conversations, the new director could easily gain a solid understanding of the company's capital structure, credit facilities, and the historical issues surrounding them, while at the same time starting the work of building a relationship with the CFO and working acquaintances with key outsiders.

In larger companies, the board may have its own consultant for one or more matters. Executive compensation comes to mind. The chairman or lead director should introduce the new director to any consultants who report to the board.

The external frame of reference brought to the board and management by independent, external directors constitutes one of their chief advantages. Providing them with an orientation process that helps them develop a rich picture of the company and its external environment improves their ability to provide the advice and counsel for which they were sought.

Build Personal Relationships

People, even experienced senior executives, are more comfortable with others when they know something about them beyond their titles and résumés. In the old days (which for corporate boards were not all that long ago), new directors were generally well known to the chairman or the CEO or one or two other directors. It was not unusual for a new director to already know every other board member. As a result, new directors had mentors or sponsors on the board who showed the new directors the ropes. Now, in an increasing percentage of cases, this is no longer the case. Many new directors know their fellow board members only through the limited exposure of the highly artificial interview process.

With independent directors joining boards in record numbers, chairs and CEOs should include opportunities for building relationships among board members whenever there is a newcomer to the group. Often we rely on the social skills that almost all directors possess to carry the day. Indeed, few people ever make it into the boardroom without good skills in getting to know colleagues. Nevertheless, the active engagement and balanced participation that mark the work of effective boards is almost always based on the mutual respect that comes from knowing good colleagues well.

Boards of directors present some special challenges, however. First, they are episodic; they meet infrequently with considerable intervals between meetings. Second, the members have full lives outside the board. Often preparing for and attending the board meetings requires considerable scheduling legerdemain. Third, pressure to perform is high. The recent regulatory and exchange requirement changes have made boardrooms less relaxed. Given that new directors and the boards they serve on want contributions sooner rather than later, building relationships among directors is worth extra thought and effort.

One new director reported that a helpful element of getting to know his new colleagues was a simple series of phone calls with each board member prior to his first meeting. Coordinated and scheduled by the chairman's secretary, the calls were only 15 to 30 minutes each. Another board took this a step further. The CEO asked each of the board members to call and introduce themselves to the new director and brief her on one aspect of board business. In addition to learning a little about each other personally, the new director learned from fellow directors their views on six or seven topics of current interest to the board. At a third company, the CEO and the new director worked only 30 miles apart.Before his first board meeting,the new director and the CEO met for lunch. A few days later, the CEO came to the new director's office to brief him on the company's assets. By the time his real board service began, the director and CEO had laid a solid foundation for working together on the board.

A number of organizations time the beginning of new directors' service to coincide with an annual board retreat. This gives the new directors a period of concentrated assimilation during which they become familiar with strategy and begin building relationships with the other board members and senior management.

Conclusion

The old boy network meant that orientation and assimilation efforts for new directors were not really necessary. New directors already knew others on the board. With the rise of the independent outsider on boards and the recent legislative and exchange requirement changes, providing an effective orientation for new directors makes sense. In fact, without a clear orientation program, organizations may find it difficult to recruit the caliber of director they need and want.

Donley Townsend is an executive search consultant and an executive coach for senior leaders new to their roles. His work includes board advisory and director search services. He may be reached at don@donleytownsend.com.

Engaging the board of directors on Strategy

By Donley Townsend

The corporate governance trailblazer, Sir Adrian Cadbury, provided a succinct description of the forces in play at the top levels of an enterprise: ‘‘The basic governance issues are those of power and accountability’’[1]. Nowhere are the issues of power and accountability more clearly in evidence than in the working out of a strategy for an organization. A firm’s strategy determines the course it will try to pursue over several years; strategy guides the allocation of resources – financial, physical, and human. Clearly, strategy must be a subject that engages the interests of all the members of a firm’s leadership – top management, the board of directors and the Chief Executive Officer.

Over the last several years, many corporate boards have sought a more substantial role for directors in the strategy-setting process. This quest has been enhanced by Great Britain’s Committee on the Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance, the Conference Board in the United States, and the US Sarbanes-Oxley legislation. The implications and repercussions of this trend will likely endure for years to come. How then can boards, Chairmen, CEOs, and top managers forge an effective process to engage directors on strategy?

Perhaps because engaging the board on strategy is a chronic concern, in practice the question of how to best manage the process is often expressed ironically or with some frustration. One Silicon Valley CEO said, ‘‘Left to their own devices, my directors will try to design new products on a napkin. How can I get them to focus on strategy?’’ The Chairman of a large Midwestern firm said, ‘‘We’re always straying off into the weeds. How can we keep our discussions strategic?’’ Another CEO at a $1 billion technology firm groaned that ‘‘these guys want me to make a major acquisition; how can I get them to s that it doesn’t fit the strategy we mapped out and agreed on eight months ago?’’ Working together with corporate leaders we’ve developed a five-point process for effectively engaging a board of directors on strategy.

Step 1: Map out a strategy agenda with the board

A key beginning point is for the CEO to work out, in collaboration with the chairman and other directors, a year-long agenda of strategy topics for board meetings. Everyone agrees that strategy work is an iterative process, not a big bang event. Yet, often we treat it as though it were a one-time event by scheduling the board’s strategy meeting or making strategy the key agenda item at the annual board retreat. Absent a rich context, directors are hard pressed to contribute effectively. Not infrequently, their contributions are destructive. That’s why it is important to have a year-long agenda of strategy topics with the board. It might look something like this:

1st Meeting of the Year – Changing Competitive Environment.

2nd Meeting of the Year – Strategic Investments: People, Plant, Equipment.

3rd Meeting of the Year – Review Achievements against Strategic Plan.

4th Meeting of the Year – Corporate Development. M&A Activities to Support the Strategy.

5th Meeting of the Year –Annual Board Retreat & Strategic Planning Workshop.

6th Meeting of the Year – Actions Individual Directors Can Take to Support the Strategy.

In developing the board’s strategic agenda, the Chairman and CEO will want to collaborate closely. One or both of them should speak one-on-one with each of the other directors to solicit their views and concerns. Whenever a CEO, Chairman, or director is new to their role, these one-on-one conversations provide an opportunity to discover the expertise of each other. Often in the course of such conversations, business leaders discover that many difficulties in strategy deliberations stem from the lack of a common vocabulary.

Mapping out the strategy process the board will follow provides time for thought, reflection, dialogue, and iteration and allows management to make meaningful use of directors expertise and knowledge.

Step 2: Describe your strategic planning process

Not infrequently, organizations run two separate strategy processes. One involves management; the second the board of directors. The intersection of these separate processes is often a presentation to the board of the results of management’s work. One Dallas-based organization, after three years of increasingly contentious debate between the

CEO and the board, opened a board meeting with a detailed explanation of how management performed its strategic planning work. The talk covered the ‘‘how,’’ not the ‘‘what.’’ The CEO and the vice president responsible for strategic planning laid out all of the work streams that were brought together to make the strategy. As the strategy VP, (who possessed deep technical expertise in planning but was new to the organization), described the process, the CEO added anecdotes about changes made over the years to improve the process and the reasons for those changes. This exposition gave the directors the ‘‘how’’ and ‘‘why’’ of management’s work on strategy. Once the directors saw that management’s process was robust, their questions shifted from challenging management’s conclusions to fostering a dialogue that extended management’s thinking. Surprisingly, the directors’ involvement led to a more aggressive and slightly more leveraged strategy. Accustomed to pushback, management had become too conservative.

A number of CEOs supplement these board-meeting presentations with phone calls to individual directors based on each director’s interests and expertise. L.J. Seven, the founder of Seven Rosen and CEO of Mostek, the pioneer integrated circuit manufacturer, regularly drew out individual directors with his understated request, ‘‘Tell me that again; I don’t get it.’’It was his way of seeking both understanding and agreement through dialogue with the director. Other CEOs use monthly letters to their board members providing the CEO’s perspective on a number of issues – some strategic, some tactical. Michael Ullman, CEO of J. C. Penney Company, composes a weekly, Sunday morning e-mail to keep his directors in the loop on strategy and execution. Whatever the method, CEOs with strong, positive board relationships keep their directors informed about both the ‘‘how’’ and the ‘‘why’’ of strategy to further their dialogue.

Step 3: Emphasize the external environment and competitive pressures

Author and law professor William Ian Miller identifies a CEO’s dilemma when deciding how much information to provide the board of directors about strategy: ‘‘God forbid one of them should start thinking deeply about this stuff and expose the limits of my knowledge’’[2]. At the heart of strategy for any reasonably complex business is our often unvoiced fear that we really don’t know as much as we let others believe we do. In presenting strategy to the board, CEOs often rely on the internal view – products, revenues, growth and plans. Less is said of the customer loyalty, marketplace discontinuity, emerging competition and disruptive technology. The danger of this approach is subtle. Given nothing but the inwardly focused view, directors’ questions tend strongly toward the inward looking plans and assumptions. From management’s perspective, such questions then seem more like intrusions into the realm of management or attacks on management’s conclusions. Either way, it makes for uncomfortable discussions.

Chairmen and CEOs who have forged an effective and collaborative path with their boards of directors focus considerable attention and board time on looking outward. The CEO of a highly successful Silicon Valley company altered his board’s perspective considerably over a period of several years. When he first joined the firm, he described the board by saying, ‘‘They are each brilliant when it comes to technology but they don’t know a thing about what general managers do. I really don’t need their help with this.’’ Realizing this was a risky approach for a new CEO, he began changing the board’s role in corporate strategy by focusing on the company’s markets. Over the course of a few board meetings, the CEO and a handful of key executives briefed the board on markets, customers and distribution channels. He followed with briefings on key competitors and invitations to directors to visit key customers and suppliers along with members of his senior team. Then and only then did he bring the agenda around to technology again. As a next step, he scheduled an hour with the board to lay out the options and alternatives management had considered during its strategic planning work. After more than a year of careful work, the CEO noted that board discussions of strategy were moving from challenge and skepticism to collaboration and contribution.

Step 4: Be clear about the required resources